How agricultural policy drives farmland drainage

by Cathy Holtslander, Director of Research and Policy

The National Farmers Union is a direct-membership organization made up of Canadian farm families who share common goals. We promote the family farm as the most appropriate and efficient means of agricultural production. Our goal is to work together to achieve agricultural policies that will ensure dignity and security of income for farm families while enhancing the land for future generations.

Thus, agricultural drainage is an issue that concerns us. Today I will focus on Saskatchewan, keeping in mind that we are part of a larger picture. Our neighbours downstream in Manitoba are directly affected by Saskatchewan’s policies, and likewise Saskatchewan farmers are affected by upstream land use in Alberta and the USA. On top of that, climate change has no borders – we are all both upstream and downstream of climate issues by our impact on the atmosphere and the changing climate’s impact on our farms. We are all in this together and need to find ways to manage our situation to reduce harm and share benefits for the common good.

Earl Butz, US Secretary of agriculture, (1971-1976)

The title of this article is based on the slogan used by Earl Butz, who was the United States Secretary of Agriculture under Richard Nixon, then Gerald Ford.

Butz was a major figure. He oversaw a fundamental shift in American farm policy from one that sought to support farmers who had suffered immensely during the Great Depression. President Roosevelt passed laws designed to deal with unsellable surpluses, market gluts, low prices and farmer poverty.

Butz not only ended these laws but shifted government support towards subsidies for large-scale commodity production for export. His policy direction is summed up by “Get big or get out”. This direction is still in place — US farm subsidies are massive, promote quantity over quality, help the big get bigger, and keep commodity prices low.

Around the same time, Canada had a similar, though less drastic change in policy direction. In 1969 a task force on the future of farming in Canada recommended reducing the number of small farmers.

The “get big or get out” mantra was repeated in the recent Barton Report, which calls for massive growth of agricultural exports. Canada’s 2017 federal Budget set up an Agriculture Economic Strategy Table, led by CEOs of global agribusiness corporations, to advance Barton’s recommendations. Here are the “key performance indicators” they propose for measuring success:

Agri-food key performance indicators for 2025

Proposed target

-

- Canada will rank in the top 10 among OECD countries for ease of regulatory burden by 2025.

- Canada will rank in the top 10 among OECD countries on the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index infrastructure category by 2025.

- Canada will have 100% broadband coverage with 100 Mbps download and 50 Mbps upload speeds by 2025.

- Canada will achieve $85 billion in exports and $140 billion in domestic sales by 2025

- Canada will increase its food industry capital expenditures per dollar of sales by 50% by 2025.

- Canada will double private-sector R&D expenditures by 2025.

- Canada will reduce the average job vacancy rate in primary agriculture to 4% by 2025, and in food manufacturing to the economy-wide manufacturing average of 2.2% by that same year.

- Canada will increase female representation in food processing industry management to 50% by 2025.

Report of Canada’s Economic Strategy Tables: Agri-food

Note that none are directed at helping farmers. Farmers are not even mentioned.

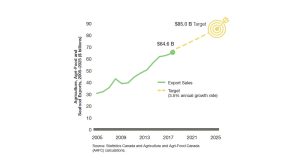

Here is the Agriculture Strategy Table’s export target:

Now let’s examine some graphs that we might call “key performance indicators” for Canada’s actual agriculture. Together I think they will help us understand why drainage is being seen by some farmers and policy makers as a solution.

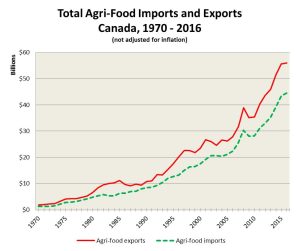

The red line in the graph to the right is the value of Canada’s agriculture and food exports. They are indeed rising! The dotted green line is our agriculture and food imports.

The increase in exports is an indicator of federal policy success. However, most of Canada’s exports are low price/high volume commodities, while our imports tend to be higher valued foods. We are importing more of our food, thus more consumer dollars are leaving Canada.

Here is where we need to take a quick look at trade agreements. When we reduce trade barriers, it goes both ways. We get access to other markets, and the other countries get access to ours too. Trade agreements also tend to harmonize regulations. This reduces the ability of any country to differentiate their products in terms of quality.

There is a lot of talk about “competitiveness” as being a good thing – often presented as a positive character trait, a moral value even. But in reality, being competitive boils down to farmers selling at ever lower prices, as global commodity traders cruise the world to source product from the cheapest locations.

Trade deals also constrain domestic policy. Farm support programs such as Agri-Stability must be “trade neutral” — which means measures that support export commodity prices for farmers are forbidden. Governments must colour within the lines – or risk a trade challenge.

(Provincial farm policy is aligned with federal policy in terms of Exports and Competitiveness via shared funding arrangements – Growing Forward, GF 2 and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership agreement. Farm support programs must comply with trade agreements. So Canada and Saskatchewan’s ag policy focus on increasing exports through “competitiveness” When selling bulk commodities there is little to compete on except for price. The lower your price, the more competitive you are)

Farmers’ debt load is increasing. Across Canada it is now over 100 billion dollars.

In Saskatchewan alone, farmers owe more than $16 billion.

Realized net income has stayed very low for decades in spite of increasing revenue.

This is an important graph, so I’ll take a little time to explain it.

The top line of the graph shows the total cash income for farmers in Canada. It has been steadily rising, as a result of increasing quantities produced and price inflation. This is the money farmers take in when they sell their products, and it also includes any farm support payments they may get. In 2018 total farm cash receipts were over $62 billion.

The top of the purple area shows realized net farm income. This is what farmers have left after paying their operating expenses and depreciation costs.

The green area between the realized net income line and the cash receipts line at the top represents the money farmers are paying others – for inputs, equipment, freight, fuel, rent, interest, accountants, etc. Most of the money in agriculture just passes through the farmer’s hands.

In 2018 realized net farm income dropped by a shocking 45%. Revenue dipped slightly and expenses went up slightly. Because farmers keep so little of the value of their crops and livestock, these small percentage changes made a huge dent in farm income. For every dollar Canadian farmers received in 2018, they kept only 6 cents.

The way 2019 is shaping up it is likely to be even worse.

Now here is the key performance indicator that we pay most attention to. It is the flip side of “Get big”. Farmers have gotten out. Some have retired willingly, but many have been forced out because it is just too hard to make a living under these circumstances.

Worse, we are not replacing older farmers with a new generation. The average age of farmers is climbing. In 2016 there were only 24,800 farmers under age 35, less than 10 percent of farmers. There are not enough new farmers starting up to take over all the older farmers’ operations when the time comes.

Let take another look at the Realized Net Income graph:

} RISK!

The gap between cash taken in and the income left to live on is very large and growing. If a person has spent a lot of money on inputs, land rent and loan payments and they don’t get the crop or the prices they had expected, it will take them several years to recover. We can consider the gap between the cash receipts and realized net income as a measure of the risk farmers take on every year.

So what can a farmer do?

When agriculture and trade policies drive down prices, farmers have to figure out strategies to keep going – to increase revenues, cut costs and/or reduce risks. There are few options:

Diversify to buffer the ups and downs of commodity prices and weather conditions. A poor year for one crop may be a good year for another; livestock can provide an income from poorer land or weather-damaged crops. Diversity can reduce disease and insect pressures and lessen need for purchased inputs such as fertilizer.

Go organic to reduce input costs and get premium prices, but yield is less certain and management can be challenging.

Increase total acres. Buying or renting more land will bring in more bushels, but it also increases costs and risks, and often requires bigger equipment and hiring workers.

Land costs are going up, partly due to farmer demand, but also because of land ownership rules and policies that allow farmland investment companies to buy up large holdings for speculation and rent extraction.

These graphs show the “get big” trend. Average farm size has been steadily increasing across Canada, and more dramatically here in Saskatchewan. The 2016 Census of Agriculture tells us that average farm size in Canada is now just over 800 acres, and in Saskatchewan, about 1800 acres.

This graph illustrates the rate of increase in average land values in Saskatchewan, with 1996 as the baseline. Some years land prices spiked dramatically. Today, farmland costs about five times what it did 20 years ago.

Here is Farm Credit Corporation’s infographic showing the increase in land prices in south-eastern Saskatchewan.

Last year land prices went up 7.4%, and price per acre ranges from $800 to $3,400.

Rented land makes up an increasing portion of farms in Saskatchewan. The yellow area in the graph below is the average area owned per farm, the green shows the average acres rented per farm.

Since around 2007, we have started seeing farmland investment companies buying large tracts of land. Cash rent provides an income for their shareholders for several years until they can sell the land to another buyer at an even higher price. This puts upward pressure on land prices due to speculation and the deep pockets of the farmland investment companies. Tax measures also put these investment companies at an advantage compared to farmers buying land.

So other strategies besides increasing your land base are to increase the income you get from your existing acres.

Increase yields with inputs by using more fertilizer and other inputs to increase revenue per acre. But this also increases costs per acre, and poor weather can wipe out potential yield gains – but not the bills.

Or you can intensify use on your existing land base. By removing bush and shelterbelts, sloughs and wetlands, you can increase the farmable acres.

Farmers’ limited survival options not only drive drainage, but also stress … economic, social, and psychological. In today’s policy environment, farmers have a lot of pressure and few choices..

We would argue that the conflict generated by farmland drainage is a key performance indicator – one that indicates policy failure.

Some farmers are responding to the “get big” imperative by disregarding the law, their neighbours, the next generation of farmers and our ecosystem.

Using drainage to convert wetlands and bush to grow high-input crops such as canola robs Nature. The living world makes it possible for human society to thrive. When we remove biodiversity, destroy habitat, change the chemistry of the soil, land, and atmosphere, we are impairing the world’s ability to reproduce. This is impoverishing, and the effects are cumulative. When the value of land is only measured by how much can be extracted from it each year, it is diminished.

The key performance indicators of farm policy that matter most to us are realized net farm income, number of farmers, farm debt. These are all going in the wrong direction. You would think our leaders in Ottawa and Regina would try to do something about it! The trouble is, farm policy IS working … for the lobbyists that have the ear of government. The big corporations are doing just fine.

For those who support “get big or get out” policy, agriculture is primarily a wealth creation and extraction process that benefits the powerful. Cargill cleared $3.2 billion last year, one of its best years ever. CN Rail had a record 2nd quarter in 2019 due to higher volumes and higher freight rates — revenues went up by $3.9 billion over last year’s. Bayer was able to pay shareholders a record dividend at the end of 2018 in spite of all the trouble stemming from its takeover of Monsanto. These are just a few of the companies that are living off the gap between farmers’ total cash receipts and their realized net income.

And its corporations like these are getting the lion’s share of economic benefit from wetland drainage.

Instead of looking at ways to further concentrate power and extract more wealth from the land, we need policy that understands that farming is how people provide food for themselves and others. It is intergenerational and cultural — knowledge is passed on, and land is cared for so that it can continue producing food for healthy populations. Returns must support the farm in a societal partnership where farmers provide needed food, and others provide things farmers need.

Record profits

Farmers are faced with difficult, often impossible choices, because they lack power. Farmers are being driven off the land by a system that IS WORKING – for the powerful

We need to reframe agriculture policy to support long-term, big picture thinking.

To retain wetlands we need to address the farm income crisis and rebuild market power for farmers. Local farmer control of land and livelihoods not only allows farmers to make a decent living, but also provides wider societal benefits. When farmers are in a position to make long-term decisions, they can put the sustainability of their farm ecosystems ahead of immediate revenues. Long-term thinking is also concerned with community-building, which enriches Canada’s diverse land-based cultures. It provides both the ability and the motivation to retain the knowledge and skills of farming in the next generation. Long-term thinking also deals with protecting the land, water and atmosphere for future generations by acting now to slow down and reverse climate change.

The NFU is an organization of farmers who call for a more just system that empowers farmers to obtain their fair share of the value and wealth they create.

OUR Key performance indicators:

-

-

- More farmers

- Younger farmers

- Higher realized net farm income

- Smaller difference between gross revenue and net income

- More land in wetlands, shelterbelts, forest, native prairie

- More diversity of crops

- Replace imported food with Canadian-produced

-

To retain wetlands we need to address farm income and market power for farmers. We need to make sure that wild lands and natural processes have the space and conditions they need to thrive. Destroying nature, frankly, is destroying ourselves.

The National Farmers Union advocates for policies that counteract excessive concentration of power. The list on the next page are a guide to the kinds of policies needed to provide fair livelihoods for farmers and promote long-term thinking, good relations among neighbours, and a commitment to working together to deal with the serious problems we will increasingly face as the impacts of climate change worsen.

“Get big or get out” policies demand ever greater extraction of value from the land, leaving less for the farmer, and eventually eliminating the farmer altogether. Who has power is important – power shapes the range of possibilities available. Drainage can be understood as a last-ditch effort to survive in a hostile policy environment.

Agriculture policies have worked against farmers’ interests by removing most of the wealth created by farmers, promoting land price increases, removing farmers’ market power. To turn things around we need good upstream policy measures. We need to reduce financial stress on farmers, support greater on-farm diversity, build and strengthen institutions for farmer power

Policies for wetland retention

-

-

- Put limits on powerful corporations’ ability to extract excess profits from farmers

- Create and rebuild institutions for orderly marketing

- Restrict on farmland ownership to residents of the province

- Support good land stewardship practices with incentives (and penalize harmful practices)

- Promote on-farm diversity to increase resilience and farmer autonomy

- Establish land set-aside and alternative land use (ALUS) programs to compensate farmers for land kept out of production

- Outlaw captive supply by meat packers, promote regenerative livestock production to improve livelihood of cattle producers

- Develop local, regional food systems to reduce imports

- Design farm support programs to help farmers survive economic and climate uncertainty, reduce reliance on unsustainable debt and help young farmers get established

-