The NFU submission to the public consultation on the Future of Competition Policy in Canada

The National Farmers Union (NFU) is pleased to provide input to the federal government’s public consultation on the future of competition policy in Canada. The consultation touches on the Competition Act, the roles of the Competition Bureau and of the Competition Tribunal.

The NFU, established in 1969, is Canada’s largest voluntary direct membership farm organization, and represents family farmers and farm workers from across the country in all sectors of agriculture. We work to promote a food system that is built on a foundation of financially viable family farms that produce high quality, healthy, safe food. We encourage environmentally-sensitive practices that will protect our soil, water, biodiversity and other natural resources, and promote social and economic justice for food producers and all people living in Canada. We promote the betterment of farmers in the attainment of their economic and social goals, and seek to increase the economic benefits of farming. Our public policy positions are developed through a democratic process of debate, initiated by grassroots members and grounded in their experience as producers.

Throughout our history, the NFU has been concerned with power imbalances between the large-scale corporations farmers deal with and the individual farmer. A Competition policy that has the tools needed to prevent excess concentration and promote effective competition would have a positive impact on many of the policy challenges faced by farmers and our food/agriculture system.

The NFU has called for Competition Bureau intervention many times throughout our history, yet we have not seen our concerns resolved. Competition has lessened, concentration has increased, and important institutions such as the Canadian Wheat Board, the Ontario Wheat Board, and the provincial hog marketing single desk agencies, which countered the market power of global agribusiness corporations, have been dismantled. While farmers produce larger quantities and higher value products than ever, the vast majority of the wealth created on our farms is being captured by highly concentrated input, farm machinery, financial, food processing and commodity trading corporations that have so far not been restrained by Canada’s competition policy. The gap between the value farmers create and the value we receive from the marketplace amounts to billions of dollars every year, some of which is compensated for by Business Risk Management and other government support program payments. The need for a strong, effective Competition Bureau is clear, and changes are long overdue.

The Competition Act can be a powerful tool for balancing the Canadian economy by tempering the positive feedback loops that lead to ever larger, more powerful corporations concentrating wealth and shaping ever larger parts of the economy through their ability to set the terms of commerce as a result of their dominance within the market. The Competition Act needs to be designed as a tool for democracy, to ensure Canadians have a diversity of meaningful and accessible ways to participate in society as producers, workers, and small business owners.

The Competition Act needs to be amended to ensure that it

- Advances public interest values that promote fair competition to support societal goals of economic fairness, inclusion and prosperity.

- Prevents harmful mergers, including by outlawing mergers that result in any company having more that 20% of market share in any sector and by removing the “efficiencies defence”.

- Prevents companies from using their dominance to exploit smaller players.

- Prevent companies from using intellectual property rights and data mining to support uncompetitive and/or exploitive behaviour.

- Provides the Competition Bureau with strong and effective investigation and enforcement authorities, including the ability to compel information from companies.

- Requires the Competition Bureau to evaluate and publish outcomes of past decisions.

- Adds the obligation and capacity to undertake and publish research on the impacts of corporate concentration and competition.

- Restructures the Competition Tribunal to ensure it can properly adjudicate a higher number of cases resulting from putting these recommendations into effect.

- Includes a fee structure that requires corporations seeking merger permission to pay their fair share of costs.

- Provides transparency and accountability to Canadians about the Competition Bureau’s work.

In addition, Canada’s Competition Policy must include adequate funding to the Competition Bureau so it has the capacity to properly serve the public interest.

The role and function of the Competition Act

The purpose of this Act is to maintain and encourage competition in Canada in order to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy, in order to expand opportunities for Canadian participation in world markets while at the same time recognizing the role of foreign competition in Canada, in order to ensure that small and medium-sized enterprises have an equitable opportunity to participate in the Canadian economy and in order to provide consumers with competitive prices and product choices. (https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-34/page-1.html#h-87829 )

Competition that is fair delivers a wide range of benefits to a society. While efficiency is one value, it cannot be the only, or primary measure for competition policy. While the term “efficiency” is not defined in the Act, it appears to be interpreted to mean reducing the cost of production and/or the potential to deliver consumer products at lower prices. Yet, a narrow view of efficiency can decrease efficiency in other ways if it offloads costs onto others, idles workers and plants, squeezes out small businesses, increases socio-economic inequality, and creates an increasingly brittle economy that lacks the redundancy needed to recover from shocks.

The Competition Act’s purpose clause should be focused on public interest values that promote fair competition to support societal goals of economic fairness, opportunity, inclusion and prosperity. The purpose should support fair prices and product choice for small and medium-sized enterprises along the value chain, and not solely for consumers. As farmers, we are acutely aware of our choices being limited and our costs rising as a result of unbalanced market power. As input buyers, farmers’ suppliers are dominated by a few large firms; as sellers we are also forced to deal with a handful of large, often global, corporations, except where it is possible to supply local small and medium enterprises or sell direct to the consumer – and even then, prices are highly influenced by the market conditions shaped by large players.

The Competition Act’s purpose must recognize the multifunctionality of economic activities: that it is possible for the framework of society’s production and consumption to be more or less aligned with social and environmental values that contribute to a political stability and inter-generational justice. A diversity of types and sizes of enterprises will contribute to resilience – and even regeneration — in the face of the multiple, emerging crises we can expect as the impacts of climate change intensify.

A properly designed Competition Act will help Canada avoid unsustainable inequality that threatens social stability and well-being for all, whether rich or poor. Research by The Equality Trust shows that less equal societies have less stable economies, and that high levels of income inequality are linked to economic instability, financial crisis, debt and inflation. (https://equalitytrust.org.uk/about-inequality/impacts ). A Competition Policy that works prevent excess concentration in the economy will promote stability, fairness and social cohesion.

Managing the tension between competition and competitiveness

A central challenge for competition policy is to recognize the difference between competition and competitiveness, and to manage their dynamics in the public interest.

The word “competitive” is often used in contradictory ways: it can be used to describe an auction barn with 50 aggressive bidders, and also to describe a large corporation, such as Microsoft, that holds a virtual monopoly on sales of its product. It is critical to recognize that the “competitiveness” of a market and the “competitiveness” of an individual firm represent different phenomena, and over time, the success of a few competitors can eliminate effective competition from their market.

Through competition, firms seek to increase their own market share, whether by producing and selling more or by increasing capacity through merger and acquisitions. As firms compete for market share, they become larger and even more competitive, while many of the smaller companies go out of business or are absorbed into larger companies. This dynamic eventually leads to just a few companies dominating, resulting in a loss of actual competition within the market due to concentration. The companies that dominate can use anti-competitive (monopolistic) practices to consolidate their position and increase their profitability. Increases in efficiency due to economies of scale do not necessarily occur, and if there are such efficiencies, it is more likely that gains will be used to further advance the companies’ goals for expansion and/or increased profits than to pass on cost reductions to others in the value chain or consumers.

The CR-4 ratio – four-firm concentration ratio – refers to the market share of the four largest firms in a market. If the CR-4 is less than 40%, a market sector is considered to be competitive; if CR-4 is above that, anti-competitive behaviour can be expected. Efficiency gains from economies of scale are not shared with customers, but captured as profits and used to further accelerate consolidation.

Canada’s Competition Act has not prevented CR-4 in key agriculture and food sectors from rising well above 40%. In ammonia fertilizer, the CR-4 is 95% – and in urea fertilizer it is 100%: the entire market is held by Nutrien, CF Industries, Koch Fertilizer, and Yara. (Nutrien Ltd., Nutrien Fact Book 2022, pp 17, 18.). In retail, Loblaw, Sobeys, Metro, Walmart, and Costco comprise 80% of the market. Meat processing for beef has just two corporations, Cargill and JBS with 99% of the federally inspected beef slaughter capacity in the Canadian market, while Canada’s CR-4 ratio for pork processing is 71% and is dominated by two companies, Maple Leaf (approximately 40%) and Olymel (approximately 10%) nationally.

The Competition Act should broaden the role of the Competition Bureau as an enforcement agency

The Competition Act needs better tools to prevent harmful mergers, and should outlaw mergers that result in any company having more that 20% of market share in any sector.

Beef packing

In 2005, when Lakeside (Tyson) and Cargill together controlled 90% of Alberta’s beef packing market, the NFU called on the Competition Bureau to stop Cargill (then Canada’s second-largest beef packer) from buying up Better Beef Ltd of Ontario, Canada’s fourth-largest beef packer (https://www.nfu.ca/policy/submission-to-the-federal-competition-bureau-regarding-the-proposed-takeover-of-better-beef-ltd-by-cargill/ ). NFU opposed this acquisition because of the clear harm it would cause farmers by eliminating Better Beef, which supported competition by providing another option for farmers selling cattle. The NFU documented the harm caused by the two big packers using captive supply (cattle they owned, or could buy from feedlots they owned) to depress prices to farmers. The NFU also demonstrated that Cargill, the largest company, could use its influence on banks to prevent smaller, independent, farmer-owned slaughter plants from getting financing. The Competition Bureau approved this acquisition anyways, claiming the relevant competition in the beef sector was global, and that the price of beef paid by consumers would not be affected by concentration in the slaughter and processing sectors in Ontario. The harm to farmers was not considered relevant. Farmers, and by extension their communities, were harmed by the loss of choice and resulting lower beef prices. The CR-4 in beef processing in Canada is now approaching 100%. Meanwhile, there is a crisis in access to local and regional abattoirs – small and medium enterprises which are the only alternative to Cargill and JBS, but which face many barriers, resulting in them not having the capacity to serve farmers and consumers who want to use their services. As beef prices paid by consumers increased faster than the inflation rate, consumers, as well as farmers and local businesses and communities continue to experience harm as a result of the Competition Bureau’s approval of Cargill’s acquisition of Better Beef nearly two decades ago.

The NFU supports amending the Competition Act to provide the Competition Bureau with the authority to restrain meat packers’ power by reversing concentration and decoupling vertically integrated packers, reversing harm caused by excessive concentration by creating conditions to ensure local abattoirs that serve markets can succeed in every region; and by enabling collective cattle marketing agencies that will ensure an efficient, fair and transparent market for both buyers and sellers.

Seed and agro-chemicals

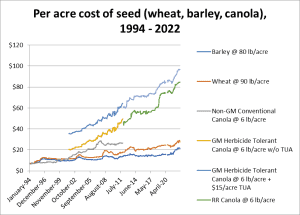

In March, 2018 the NFU gave input to the Competition Bureau supporting our opposition Bayer’s acquisition of Monsanto. (https://www.nfu.ca/farmers-lose-with-usas-canadas-approval-of-bayer-acquisition-of-monsanto-says-nfu/ ) We provided information about concentration of the canola market in Canada to illustrate how Bayer and Monsanto have expanded their market share and increased seed prices to farmers in ways that appear more collaborative than competitive. We noted that there is no incentive for companies to use innovation to improve products when they already fully control the market. Instead, they use tools such as GMO patents to extract higher rents in the form of seed prices, technology use fees, and data mining.

We recommended that Bayer and Monsanto should not be permitted to merge even with the condition that Bayer had to sell its seed and chemical business to BASF, as this did not change the dynamics of this highly concentrated market significantly. We urged the Competition Bureau to use their decision-making power as an opportunity to reduce the dominance of these few companies by requiring Bayer and Monsanto’s seed and agro-chemical divisions to be broken up into smaller entities. However, Bayer was allowed to acquire Monsanto, and today, farmers still lack choice and pay excessively high prices for seed and other inputs sold by these globally dominant corporations.

The graph above shows per-acre seed prices in Alberta from 1994 until 2022. Canola prices began rising above wheat and barley prices soon after the introduction of patented, genetically modified (GM) canola varieties. Following Bayer’s acquisition of Monsanto, the price of GM Roundup Ready canola seed increased rapidly, and both it and GM Liberty Link canola seed prices continue rise faster than other seed costs. This indicates an abuse of dominance, which the NFU predicted, but the Competition Bureau was unable to prevent, and is unable to remedy after the fact.

The Competition Act should also prevent companies from using intellectual property rights to support uncompetitive behaviour. A combination of market dominance and the use of patent rights to prevent farmers from saving and planting seed from the crops they grow on their own farms has forced them into buying seed and paying royalties to Bayer and BASF if they want to grow canola.

Fertilizer

The Competition Bureau has also failed to prevent anti-competitive behaviour resulting from fertilizer industry consolidation. The Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan and Agrium merged in 2018 to form Nutrien which now has 44% of Canada’s ammonia market and 46% of the urea market. In 2022 farmers fertilizer costs increased by 80% (https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/2413-growing-and-raising-costs-farmers ) and while companies blamed supply chain issues due to the war in Ukraine and Covid 19, these same companies are making huge windfall profits. In their 2021 annual report, Nutrien, notes “record financial results” and reports fourth quarter net earnings nearly four times higher than a year ago. (https://nutrien-prod-asset.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2022-02/Nutrien%20Q4%202021%20Presentation%202022-02-16%20FINAL_2.pdf) CF Industries, Canada’s second largest producer, reports fourth quarter net earnings nearly eight times higher than a year ago. (https://cfindustries.q4ir.com/news-market-information/press-releases/news-details/2022/CF-Industries-Holdings-Inc.-Reports-Full-Year-2021-Net-Earnings-of-917-Million-Adjusted-EBITDA-of-2.74-Billion/default.aspx) Yara International, also with significant Canadian capacity, reports that for its operations in the Americas, “EBITDA [Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization] excluding special items was 160% higher than a year earlier, as increased nitrogen prices more than offset higher energy costs…” (https://ml-eu.globenewswire.com/Resource/Download/9d271a64-fb0a-46c1-8729-7ec5f3bc88f0 ) In many cases, the companies posted these higher net returns on lower production and sales volumes. These facts point to anti-competitive behaviour and abuse of dominance. The Competition Bureau has not been able to address these negative consequences of the concentration in the fertilizer sector that has happened under its watch.

We would like to see the Competition Act amended to require evaluation of outcomes of past decisions such as these beef packing, seed and agro-chemical and fertilizer merger decisions. Where decisions have proven harmful, the Competition Bureau must have the authority to order effective remedies.

Greater research capacity and stronger investigation and enforcement authorities needed

The Competition Bureau needs strong and effective investigation and enforcement authorities, including the ability to compel information from companies, along with the obligation and capacity to undertake and publish research on the impacts of corporate concentration and competition.

Corporate consolidation is being accomplished in emerging ways that are more difficult to detect than measuring the CR-4 ratio in sectors. Increasingly, corporations are building complex architectures of inter-connection through technology licensing and data sharing agreements. Their ability to exert control in the marketplace may stem from these arrangements, rather than from outright ownership of companies. This could be considered a form of “three-dimensional” integration that is less visible, but more powerful, than the vertical and horizontal integration we are more familiar with. Authority to compel information for purposes of investigation and research is needed to understand their implications for competition. Companies using such arrangements may never seek to formally merge, but their ability to avoid competition and collude with other firms in the same economic space will be experienced by the economy.

The current Competition Policy review highlights the outsized impact that small digital companies can have on competition, which is relevant here as well. Purchasing a popular app from a digital ag start-up company may not increase a large firms ownership footprint, but could substantially increase its capacity to abuse its dominance. The NFU is pleased that the impacts of the digital technology space it being examined in this review.

The Competition Bureau needs to have the tools, authority and capacity to investigate the impacts of these arrangements.

Loss of competition through third-party investor influence

The Competition Bureau also needs to have the power to research, investigate and address the role of asset management firms that invest in multiple key players in a sector. The table below, from Food Barons 2022, Crisis Profiteering, Digitalization and Shifting Power, by ETC Group (https://www.etcgroup.org/files/files/food-barons-2022-full_sectors-final_16_sept.pdf ) indicates the potential for these investors to simultaneously influence, or even drive, strategic decisions by major corporations in the food and agriculture space. The Competition Bureau needs to include these dynamics in its assessments of anti-competitive behaviour and abuse of dominance.

Addressing challenges of data and digital markets

The Competition Bureau needs to be equipped to deal with the impacts of big data on competition. Big Data is an emerging concern for farmers. As new technologies are developed, such as precision farming equipment and smart phone marketing apps, farmers are providing huge quantities of data without knowing who has access to it or how it is used. An individual farmer’s ability to deny access to their data has little impact on the market power big companies can gain from these tools. Companies that have access to aggregate data can use the information in ways that increase the power imbalance between them and the individual farmer. There is little to no information about the impacts or implications of data mining on competition. The Competition Bureau needs authority to compel information that will allow it to investigate how these data applications are used. The Act also needs to include authority to order measures that create clear limits on how data is collected and used, as well as the tools to enforce these measures.

The Competition Tribunal

Canada’s competition policy needs to restructure the Competition Tribunal to ensure it can properly adjudicate a higher number of cases resulting from putting these recommendations into effect. The tribunal is a quasi-judicial body that specializes in hearing competition cases. This body must be equipped to operate in the public interest, to ensure that the range of perspectives brought to bear on decisions reflects the interests of those affected by potential harms.

Fees and funding

As a public interest body serving Canadians, it is necessary for the Competition Bureau to have the resources it needs to do its job properly. Public funding allocations should be adequate to ensure the Competition Bureau can take on research and investigation, particularly in horizon scanning for emerging issues and in developing strategies to prevent and redress harms from excess concentration.

The companies involved in the kinds of large-scale mergers that are of greatest concern are very wealthy, and are strongly motivated to spend money on advancing their private interests. The Canadian taxpayer should not have an inordinate burden for paying the costs of examining and dealing with the implications of mergers and acquisition decisions that are made by and for private companies. The fees paid by companies seeking approvals must reflect their fair share of the costs.

Transparency and Accountability

Few Canadians are aware of the work of the Competition Bureau, even though its decisions have a profound effect on their lives as individuals and collectively. The Competition Act should be amended to require an annual report to Parliament of its work, presented in enough detail and with clarity to ensure it is accountable to Canadians. A public registry of decisions that is easily searchable, as well as a mechanism for Canadians to provide information and raise concerns to assist the Competition Bureau in its work, should be established.

All of this respectfully submitted by

The National Farmers Union

March 31, 2023