In this issue:

- Artificial Intelligence Will Not Feed Us, Artificial Intelligence is no Substitute for Public Agronomists

- Don’t let the grocery giants fool you: food price inflation is not the farmer’s fault

- NFU Pre-Budget Consultation Submission

Artificial Intelligence Will Not Feed Us, Artificial Intelligence is no Substitute for Public Agronomists

—by Sarah Marquis, NFU Outreach Strategist

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) throughout society has been hard to miss. It is having an impact on every sector, from healthcare to education, from law to the creative arts. The federal government has recently appointed a Minister of AI, Evan Solomon, who has compared the development of AI to the invention of the printing press, expressing an unbridled enthusiasm for the technology. Though AI in agriculture does not get quite as much attention as in other industries, it is still deeply important to think about. Given the decline of extension services across the country and the many challenges facing Canadian farmers, AI is purported to be an all-in-one solution that will help farmers with the day-to-day operation of their farms. However, it is important to understand the impacts of AI tools before letting them replace human-centred agriculture extension services altogether.

Farm Credit Canada (FCC), an agricultural financial services organization and federal Crown Corporation, recently launched a tool called Root, a “generative AI tool custom-made for the Canadian agriculture and food industry…” FCC promises Root will provide “practical advice, smart recommendations and personalized solutions to help you navigate the complexities of modern agriculture…” Root marks a definitive turn towards AI as a tool to fill the gap caused by years of budget cuts to provincially and federally funded extension services. Root is a large language model (LLM) — an AI chatbot. It can answer questions and provide recommendations to farmers with questions about, for example, what to plant and what kinds of inputs to use. And while using a chatbot might be useful in some contexts, it would still be risky to ask it for things like medical or financial advice. The stakes are high in agriculture as well. Inaccurate AI-generated recommendations from a tool like Root could have serious consequences that could lead to the loss of crops, the death of livestock, and financial ruin for farmers.

Furthermore, while the recommendations generated by AI tools may seem objective and true, these tools have built-in bias. Users cannot know how and why these recommendations were generated because the process AI uses to compose responses is non-transparent and cannot be traced or verified. Given corporate consolidation of wealth and power in agriculture and the resulting influence this has on funding the research used by a tool like Root, this LLM could provide recommendations and advice in line with corporate interests, rather than the specific needs of the farmer. Use of these tools could further entrench corporate interests in agriculture, deepening farmer dependency on multinational agricultural corporations.

It is also important to understand the material impacts of AI tools. They depend on extensive computational power and data storage requirements that are driving rapid construction of hyper-scale data centres across the globe. These data centres remotely store and process the vast amount of data required by AI models, specifically LLMs like Root. These data centres are often built on rural land, and sometimes even on land that has been zoned for agriculture. Furthermore, they take a heavy environmental toll, requiring a huge amount of (often fossil fuel) energy and water to operate. Farmers experienced severe climate change impacts across the country this past summer with wildfires, droughts, and unpredictable growing seasons. All evidence suggests that the use of AI would exacerbate these problems.

AI tools like Root are not a dependable solution to the problems that farmers face in Canada. Farmers need reliable extension services that support knowledge sharing and local relationship-building. This could be achieved through the establishment of a Canadian Farm Resilience Agency, which would provide support for independent agronomists working with and supporting farmers in their endeavours to be more sustainable, resilient and economically viable. Above all, technological interventions, whether they be AI-driven LLMs or anything else, should centre the needs of farmers and farm workers.

Don’t let the grocery giants fool you: food price inflation is not the farmer’s fault

—OP ED by James Hannay, NFU Policy Analyst

Canadians are upset about higher grocery bills, but most farmer incomes have not kept up with inflation. So what is driving prices up at the grocery stores?

Many organizations and consumers point to corporate greed as the cause. While Canadians have had to spend more for less across a variety of commodities since 2020, inflation in the retail grocery sector continues to be higher than in other sectors.

Retail grocery companies’ revenues increased despite a decrease in the volume of food purchased by Canadians. Canadian retail grocers continue to see higher profit margins compared with pre-pandemic levels. Grocers are able to take advantage of inflationary periods to increase profits because of the market power they have: five grocery chains control 75% of the market. Shoppers have few choices, making it easier for retailers to raise prices without losing customers.

In response to a Parliamentary study on rising grocery prices, the grocery chains’ lobby group, the Retail Council of Canada, claimed that: “The combined roles of cost spikes for feed, fuel, and fertilizer, compounded by supply chain disruptions, labour shortages and climate events have been the real drivers of food price inflation and higher costs.”

If that is true, prices paid to farmers should have increased more than the general rate of inflation. Data compiled by the National Farmers Union shows that they have not.

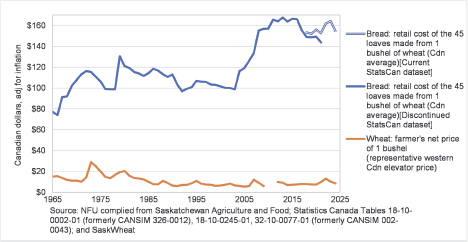

Over the past 30 years the retail price of bread has increased 50%, while Canadian farmers have not seen an equivalent increase in the price of the wheat that they sell at the elevator. The value of farm products has decreased relative to other consumer items. It takes more bushels of wheat to buy a pair of work boots or a house than it did fifty years ago. For example, a top-line, base model pickup truck was equivalent to about 2,000 bushels of wheat in 1976. Today, that truck would cost the farmer 7,000 bushels.

This decline in relative value is apparent among other commodities. The retail price of ground beef has doubled since 1994 while the price farmers receive for cull cows used to make hamburgers has increased by just 40%. While the farmers’ price for steers is increasing, the increase in the retail price of steak continues to outpace growth in farm prices. The farm price of hogs compared to bacon and pork chops shows a similar pattern. For all these commodities, the consumer is paying more while the farmer is receiving less. More importantly, beef and pork markets are highly volatile—prices for farmers have crashed several times in the last two decades.

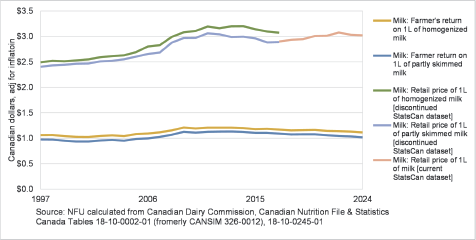

However, supply management, which governs the production of dairy, eggs, chicken, and turkey provides more stability and better outcomes for both farmers and consumers.

Retail prices for milk have increased more slowly than other grocery prices. Compared to other products such as bread and ground beef, milk prices rose by only 27% over the last thirty years. When you buy milk at the grocery store, 30% of what you pay supports Canadian farmers – the farmers’ share of the consumer’s dairy dollar has remained stable. This is true for eggs and chicken as well, where farmers also receive roughly a third of the retail price. For supply managed products, consumer prices have risen slower than for other foods, while the farmer’s share has remained consistent, even though retailers set their own prices – farmers have no control over prices after the product has left their farms.

Supply management shows it is possible to provide a fair share to farmers and a fair price for consumers. Under supply management, a formula using data from a survey of actual farmers’ production is used to determine a price that covers production costs, ensuring farmers can stay in business producing the food Canadian consumers need.

Production discipline ensures farmers produce enough – and not too much – of their product according to their share of the national quota. Import controls make sure that excess product does not flood the market, depress prices, and lead to waste. Each province has its own share of the national quota managed by its own marketing board. This means that processing facilities for dairy, egg, chicken, and turkey products are distributed across Canada, guaranteeing that consumers have local products no matter where they live. The high quality and predictability of supply keeps processing and distribution costs down too.

In non-supply managed sectors prices are not determined by their cost of production. Traders buy from farmers at the lowest price possible. Because individual farmers do not have bargaining power they are exposed to big companies’ market power. These companies keep commodity prices down in order to keep their profits up. Grain, beef and pork farmers are at the mercy of the margin-maximizing “buy low – sell high” strategies of commodity traders. Increasing market power allows ever-larger traders to take a bigger bite out of food processors’ bottom line, who in turn pass on this cost increase to wholesalers, and then to retailers.

Supply management keeps food dollars in Canada and protects against tariffs or currency exchange rate shocks. It supports fair incomes for farmers, provides for processing efficiency, and ensures consumers have reliable access to high-quality Canadian food at fair prices.

Farm prices are not driving grocery costs, corporate greed is. Farmers deserve a fair share of food prices. The success of supply management provides clear evidence that this is possible.

NFU Pre-Budget Consultation Submission

—by Cathy Holtslander, Director of Research and Policy

The federal government will soon be tabling its first budget since the election. The NFU participated in the pre-budget consultation to provide input on priorities to address the unprecedented challenges facing our country. Our focus is on building food sovereignty – a critical element in maintaining Canada’s economic and political independence. We argue that drastically cutting the federal government’s capacity — by cutting operating budgets by 7.5% this year and reaching 15% over the next 3 years, along with a major push to deregulate and offload responsibilities — is the wrong approach in the midst of major crises.

Canadians’ determination to resist American aggression goes beyond economics. The American administration has turned to authoritarianism, racism, violence and lawlessness, and seems to thrive on cruelty and destruction. In Canada, mounting inequality makes us more vulnerable to American economic warfare. If the federal government goes ahead with drastic cuts, Canada’s ability to reduce inequality, serve rural, remote and marginalized people, and solve big problems that require a focus on the public interest will be hampered. We call for public investment in food sovereignty to make agriculture a source of stability, security, resilience and community prosperity and will help Canada build up the true wealth of our nation: our people.

Our budget recommendations:

- Increase federal operational and regulatory capacity to address multiple crises, including American threats to Canadian sovereignty.

- Increase funding for food and agriculture regulators, ensure they are free from regulatory capture and have the mandate and capacity to properly enforce public interest regulations. This is critical in light of Canada’s over-dependence on food imports from the USA while the American government is dismantling its food safety and health regulatory bodies.

- Establish a federal research and agricultural extension institution for farmers, scientists and agronomists to jointly identify and solve climate change mitigation and adaptation-related problems. We need to counteract anti-climate action PR campaigns and create effective ways to deal with climate impacts on farms.

- Design a new suite of support programs to support food sovereignty based on the multifunctionality of agriculture. These programs would increase Canada’s capacity to produce, process, store and distribute food for domestic consumption in order to ensure a reliable supply of nutritious, high-quality food for residents of Canada; safeguard farmers’ incomes; advance GHG mitigation and support adaptation to climate change impacts on farms and agricultural infrastructure; enhance biodiversity, water quality/conservation and toxicity reduction; promote social inclusion and diversity of farmers and food sector workers; promote successful establishment of young and new farmers; and enhance rural community vibrancy and rural quality of life.

- Establish a national local food purchasing procurement framework in partnership with provincial and municipal governments. It would be modelled on a very successful Brazilian program that promotes equity and supports sustainable farms to supply schools, hospitals, prisons and other public facilities.

- Develop an agricultural workforce strategy to address domestic food production and support economic dignity of resident and migrant workers. This recognizes that we will need more, not fewer workers in a food sovereignty-based system, and their jobs need to be good jobs.

- Enhance Supply Management marketing boards’ capacity to add new entrants and alternative production/processing opportunities.

- Increase funds for public plant breeding. We must keep pushing back against the privatization of plant breeding and defend our plant breeding institutions from cuts.

- Create a public registry of beneficial ownership of all farmland so that wealthy individuals who control farmland investment funds cannot hide behind entities like numbered companies,

- Create tax disincentives to reduce farmland inflation caused by farmland investment speculation.

- Regulate Artificial Intelligence (AI) using the precautionary principle both within government and broadly in Canada as a whole, and develop a legal framework for agricultural data governance to address the power imbalance between individual farmers and the large corporations that aggregate big data for their own benefit.

This article is a brief summary. To read our entire submission, visit the NFU website and look under the Policy and Reports tab.